Formulating Objectives and Learning Introduction

Sabria Ali Mohamed

Introduction

When a ship’s navigator loses direction due to a malfunction in the navigation equipment, the ship may end up docking in a dangerous place, a safe place, or may never reach any destination at all. The same applies to a teacher when instructional objectives are absent.

The topic of defining and formulating instructional objectives for the purposes of teaching and evaluation has become one of the vital issues directly connected to the educational process. The process of teaching and learning provides students with learning experiences aimed at achieving specific objectives. These objectives are what guide and direct the instructional activity, and consequently determine its content.

Therefore, without clear instructional objectives, a teacher cannot plan any teaching activity in a correct, scientific, and organized manner. Then, defining and formulating instructional objectives clearly and explicitly is considered one of the first and most important steps in the teaching process. In this regard, Davis points out in his well-known statement that “there is no single step in education or vocational training more important than writing instructional objectives for learning purposes.” If this step is done properly, it will make a significant contribution to the success of the instructional process in the following ways:

- It provides a clear guide that the teacher can rely on at various stages of instruction, especially when selecting teaching materials, methods, and suitable educational benefits.

- It clearly defines the purpose of teaching.

- It forms the basis for designing tests and other evaluation methods.

- It facilitates the learning process, especially when students know what is expected of them to learn.

- It gives the beneficiaries (such as employers or institutions) a clear understanding of the skills expected to be acquired by graduates upon completing their studies.

The Relationship Between Learning Outcomes and Learning Experiences

Objectives and Learning

The word “objective” has been used since ancient times and originally meant any general direction or aim - such as improving success rates or raising students’ achievement levels. These phrases were, until recently, considered as objectives, while in reality, they were merely general guidelines.

The concept of objectives changed with the emergence of the theory of “Management by Objectives (MBO)” in the field of administration, coinciding with the appearance of the

“Taxonomy of Educational Objectives” in the field of education. Since then, the concept of objectives has gained a new dimension, creating a major shift in many prevailing administrative and educational concepts.

This new dimension is determined by the content of the objective, the way it is formulated, and its role in the planning process. In terms of content, the objective now includes specific details that must be written in a particular way. In terms of planning, no administrative or educational process can be properly planned without objectives that meet these specifications.

From a psychological perspective, education is defined as a process intended to bring about changes in students’ behavior. Each student possesses a set of behavioral patterns - or what is called behavioral inputs - before entering any stage of education. Based on this definition,

education aims to modify these behavioral patterns by either developing and enhancing some of them, acquiring new patterns, or adjusting existing ones. Accordingly, the teaching or instructional process is defined as a measured and planned process aimed at creating changes in students’ behavior as a result of going through a specific curriculum or educational program.

It is clear that the focus in these definitions is on the word “behavior” In educational terminology, this word is used to describe the effect of an action that may be physical, mental, or emotional. This use differs from the common usage of the word, which often refers to a

person’s good or bad manners. Learning can thus be defined as a relatively permanent change in behavior resulting from the student’s acquisition of experience, training, or practice. As a teacher, your task is to provide appropriate learning experiences to students in order to achieve the desired and intended behavioral changes.

Therefore, it is logical to say that before planning any teaching activities, you must have a clear idea of the intended learning outcomes-what you expect the student to learn. Hence, defining objectives in advance and on a behavioral basis becomes an essential and urgent process.

When you identify the expected learning outcomes before teaching, you are in effect writing instructional objectives. Thus, instructional aims can be defined as clear descriptions of the expected learning outcomes or the student’s anticipated performance at the end of a specific instructional period. This period may be a one-hour lecture, a teaching unit, or an entire course.

Once the instructional objectives are written based on the expected learning outcomes, the teacher can then plan and select appropriate methods and learning activities that will lead students toward achieving those objectives, and later measure the extent of their achievement through assessments.

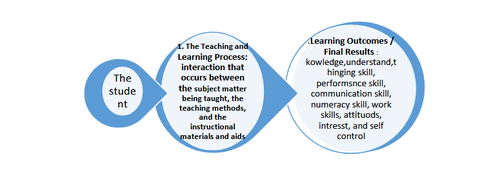

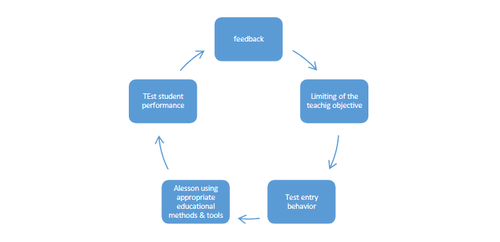

The diagram below represents a basic teaching model that illustrates the points we have mentioned

After formulating instructional objectives, the teacher should limit whether the students possess a sufficient level of knowledge and skill that enables them to understand the lesson. This is known as entry behavior, which describes the student’s level before instruction begins. After assessing this, the teacher begins the teaching process, using the available instructional materials and methods based on the nature and type of objective. Next, the teacher needs to determine how much the students have actually learned. This requires measuring student performance by conducting tests to identify the extent to which the instructional objectives have been achieved. Based on the test results, the teacher can then make necessary adjustments to the teaching steps (1, 2, and 3).

- Educational Objectives and Instructional (Teaching) Objectives

It is important here - to avoid confusion that often happens - to distinguish between educational objectives and instructional (teaching) objectives. The term “educational objectives” refers to the broad, general goals of the educational system that reflect the

philosophy of education. Objectives at this level are highly abstract, general, and complete, describing the final destination of an entire educational program or stage.

Here are some examples of statements that represent this type of objective:

Instructional Objectives

Instructional objectives - sometimes called specific objectives or behavioral objectives - as previously defined, refer to the specific patterns of student performance. They are narrower in scope and more specialized than educational objectives. Instructional objectives can be written at different levels - for an entire course, a teaching unit, or even a single topic within a unit.

Examples include:

- Recognizing the letters of the alphabet.

- Distinguishing between similar letters.

- Identifying conductive and non-conductive materials.

Methods of Writing Instructional Objectives

Since instructional objectives must be clear, explicit, and unambiguous, giving the same meaning to everyone who reads them, there are two main methods to achieve this clarity:

- Writing all instructional objectives using terms that describe only the specific, observable, and measurable behavior that represents a learning outcome.

- Using general, non-determinate terms to describe the expected learning outcomes, and then clarifying each outcome by selecting a sample of specific behaviors that can be accepted as representatives of that outcome.

The first method was developed by Mager, while the second method was proposed by Grönlund. Both methods are useful in technical education, as certain situations are better suited to Mager’s approach, while others may require Grönlund’s.

Despite their differences, both methods share some common foundations:

- The objective must be clear and specific.

- The objective should be stated in terms of student performance, such as repairing a device, assembling equipment, operating a machine, solving a problem, identifying errors, defining, explaining, or describing something.

- The objective must be written from the student’s perspective, not the teacher’s -for example: “The student should be able to distinguish between differences and similarities in …”

- The statement of the objective should include an action (behavioral) verb.

Mager’s Method for Writing Instructional Objectives

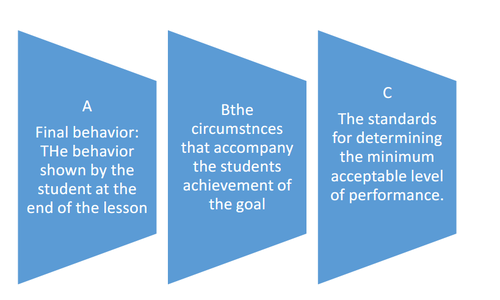

Mager proposed that an instructional objective should express what the student will be able to do to demonstrate mastery of the objective. He identified several essential elements that must be included in writing an instructional objective:

Therefore, Mager believes that it is not always necessary for an instructional objective to contain all three of the elements mentioned above. However, some specialists in this field - most notably Grönlund - argue that including the conditions and performance standards is preferable, as it improves the quality of the objective. Ultimately, this decision is left entirely to the

teacher’s judgment. A teacher may find it unnecessary to define the conditions in advance, just as there are no fixed scientific rules for determining performance standards, since such standards may already be established within the exam or evaluation system.

a. Terminal Behavior (Final Behavior):

This refers to the performance or action that the student will demonstrate after instruction. Therefore, the objective must include behavioral terms (action verbs). Verbs such as “know” or

“understand” are not suitable for describing terminal behavior according to Mager’s method of writing instructional objectives.

b. Conditions:

These refer to the materials, tools, references, or other resources provided to the student that are needed to perform the objective. Conditions may also specify the type or duration of the test or task.

Examples:

- Within a one-hour session.

- When laboratory equipment is available.

- When the student is given a device to measure electric current.

- Using engineering drawing tools.

- Without using a slide rule (calculator).

c. Standards (Criteria):

These specify the minimum acceptable level of performance. The performance standard may be based on:

- Speed (e.g., completing the task within one hour),

- Quality (e.g., meeting specific standards or accuracy levels),

- Quantity (e.g., answering 8 out of 10 questions correctly), or

- Precision (e.g., completing the task without errors)

Example Demonstrating the Three Elements in Mager’s Method:

When the student is given a 30-amp DC motor containing a single fault and provided with standard tools and references, the student will be able to repair the motor within 45 minutes. This objective, written according to Manger’s method, contains:

- The verb “repair”, which describes the desired terminal behavior.

- The phrase “when the student is given a motor…”, which specifies the conditions under which the behavior will occur.

- The phrase “within 45 minutes”, which indicates the performance standard required.

2. Grönlund’s Method for Writing Instructional Objectives

Grönlund believed that classroom teaching is largely aimed at helping students understand basic principles and concepts that they can apply in a variety of situations - not just in one or two specific contexts. He also emphasized that teaching should focus on developing students’ abilities in critical thinking, problem-solving, and other higher-order cognitive skills. As an attempt to maintain the integrity of the subject matter as a unified whole for instructional purposes — while still ensuring measurable student performance- Grönlund proposed writing instructional objectives at two levels:

A. General Instructional Objectives

These represent broad learning outcomes - what the student is expected to understand or appreciate after instruction.

B. Specific Instructional Objectives

These are behavioral objectives that relate to each general instructional objective and serve to clarify and exemplify it. Grönlund stressed that the teacher should focus primarily on achieving

the general instructional objectives, while the specific behavioral objectives should serve as the basis for assessments and testing.

Examples

Example 1

General Instructional Objective:

The student understands Newton’s Law of Motion. Specific Instructional Objectives:

- States Newton’s Law of Motion.

- Defines force, momentum, action, and reaction.

- Explains the units of force.

- Derives the relationship between force and momentum.

Example 2

General Instructional Objective:

The student realizes the importance of using insulating materials in construction. Specific Instructional Objectives:

- Correctly defines insulating material.

- Identifies different types of insulating materials.

- Distinguishes between insulating and non-insulating materials.

- Determines the benefits of using insulating materials in buildings.

Notice that verbs such as knows, understands, and realizes — which were previously considered unsuitable for behavioral objectives — are now used appropriately when formulating general instructional objectives. The general objective, in this sense, describes a broad learning outcome that is not directly observable, but can be clarified and demonstrated through a set of specific instructional objectives. Also note that the phrase “The student should be able to…” is no longer repeated before every objective, since it is already understood that the performance refers to the student.

Additional Example:

When all the required equipment is available in the laboratory, the student will be able to perform the experiment completely.

Examples and Flexibility in Writing Instructional Objectives

- Within a one-hour session, the student will be able to answer 80% of the questions correctly.

- When given a faulty television set, the student will be able to:

- Identify the location of the malfunction.

- Select the appropriate tools and equipment needed for repair.

- Repair the fault within 30 minutes.

- The student will correctly classify soil samples when given a specimen.

In the above examples, different styles have been used to formulate instructional objectives. This means that a teacher does not have to adhere to a fixed formula or sequence when writing objectives. The teacher can express the objective in any suitable way, provided that this does not compromise the essential elements of a well-structured instructional objective, as previously discussed.

Writing Specific Instructional Objectives According to Grönlund’s Method

- Write the general instructional objective first.

- Begin each specific instructional objective with an action verb that describes the student’s final (observable) behavior.

- Write the specific instructional objectives that are relevant to and clarify the general objective.

- Include conditions and performance standards when necessary.

- Provide several specific instructional objectives for each general objective to illustrate the different types of behaviors required to achieve it.

- Each specific instructional objective should express one learning outcome only.

- Arrange the specific objectives in a logical sequence, so that achieving the first becomes a prerequisite for achieving the next, and so on.

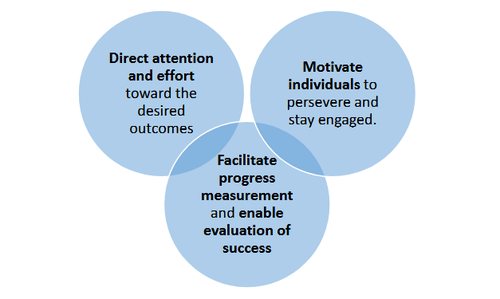

Objectives in the Context of Learning

Objectives are the clearly defined goals that learners strive to achieve. They play a central role in the learning process because they:

- Direct attention and effort toward the desired outcomes.

- Motivate individuals to persevere and stay engaged.

- Facilitate progress measurement and enable evaluation of success

The relationship between goals & learning